Your Chapter 2 title

Introduction

Your introduction (if any) here.

Chapter Outline

Your table of content here.

DATATOOL source code is located at c++/src/serial/datatool; this application can perform the following:

Note: Because ASN.1, XML and JSON are, in general, incompatible, the last two functions are supported only partially.

The following topics are discussed in subsections:

Invocation

The following topics are discussed in this section:

Main Arguments

See Table 1.

Table 1. Main arguments

| Argument |

Effect |

Comments |

| -h |

Display the DATATOOL arguments |

Ignores other arguments |

| -m <file> |

module specification file(s) - ASN.1, DTD, XSD or JSON |

Required argument |

| -M <file> |

External module file(s) |

Is used for IMPORT type resolution |

| -i |

Ignore unresolved types |

Is used for IMPORT type resolution |

| -f <file> |

Write ASN.1 module file |

|

| -fx <file> |

Write DTD module file |

“-fx m” writes modular DTD file |

| -fxs <file> |

Write XML Schema file |

|

| -fjs <file> |

Write JSON Schema file |

|

| -fd <file> |

Write specification dump file in datatool internal format |

|

| -ms <string> |

Suffix of modular DTD or XML Schema file name |

|

| -dn <string> |

DTD module name in XML header |

No extension. If empty, omit DOCTYPE declaration. |

| -v <file> |

Read value in ASN.1 text format |

|

| -vx <file> |

Read value in XML format |

|

| -vj <file> |

Read value in JSON format |

|

| -F |

Read value completely into memory |

|

| -p <file> |

Write value in ASN.1 text format |

|

| -px <file> |

Write value in XML format |

|

| -pj <file> |

Write value in JSON format |

|

| -d <file> |

Read value in ASN.1 binary format |

-t argument required |

| -t <type> |

Binary value type name |

See -d argument |

| -e <file> |

Write value in ASN.1 binary format |

|

| -xmlns |

XML namespace name |

When specified, also makes XML output file reference Schema instead of DTD |

| -sxo |

No scope prefixes in XML output |

|

| -sxi |

No scope prefixes in XML input |

|

| -logfile <File_Out> |

File to which the program log should be redirected |

|

| conffile <File_In> |

Program’s configuration (registry) data file |

|

| -version |

Print version number |

Ignores other arguments |

Code Generation Arguments

See Table 2.

Table 2. Code generation arguments

| Argument |

Effect |

Comments |

| -od <file> |

C++ code definition file |

See Definition file |

| -ods |

Generate an example definition file (e.g. MyModuleName._sample_def) |

Must be used with another option that generates code such as -oA. |

| -odi |

Ignore absent code definition file |

|

| -odw |

Issue a warning about absent code definition file |

|

| -oA |

Generate C++ files for all types |

Only types from the main module are used (see -m and -mx arguments). |

| -ot <types> |

Generate C++ files for listed types |

Only types from the main module are used (see -m and -mx arguments). |

| -ox <types> |

Exclude types from generation |

|

| -oX |

Turn off recursive type generation |

|

| -of <file> |

Write the list of generated C++ files |

|

| -oc <file> |

Write combining C++ files |

|

| -on <string> |

Default namespace |

The value “-“ in the Definition file means don’t use a namespace at all and overrides the -on option specified elsewhere. |

| -opm <dir> |

Directory for searching source modules |

|

| -oph <dir> |

Directory for generated *.hpp files |

|

| -opc <dir> |

Directory for generated *.cpp files |

|

| -or <prefix> |

Add prefix to generated file names |

|

| -orq |

Use quoted syntax form for generated include files |

|

| -ors |

Add source file dir to generated file names |

|

| -orm |

Add module name to generated file names |

|

| -orA |

Combine all -or* prefixes |

|

| -ocvs |

create “.cvsignore” files |

|

| -oR <dir> |

Set -op* and -or* arguments for NCBI directory tree |

|

| -oDc |

Turn ON generation of Doxygen-style comments |

The value “-“ in the Definition file means don’t generate Doxygen comments and overrides the -oDc option specified elsewhere. |

| -odx <string> |

URL of documentation root folder |

For Doxygen |

| -lax_syntax |

Allow non-standard ASN.1 syntax accepted by asntool |

The value “-“ in the Definition file means don’t allow non-standard syntax and overrides the -lax_syntax option specified elsewhere. |

| -pch <string> |

Name of the precompiled header file to include in all *.cpp files |

|

| -oex <export> |

Add storage-class modifier to generated classes |

Can be overriden by [-]._export in the definition file. |

Data Specification Conversion

When parsing a data specification, DATATOOL identifies the specification format based on the source file extension - ASN, DTD, XSD, JSD or WSDL.

Scope Prefixes

Initially, DATATOOL and the serial library supported serialization in ASN.1 and XML format, and conversion of ASN.1 specification into DTD. Compared to ASN.1, DTD is a very sketchy specification in the sense that there is only one primitive type - string, and all elements are defined globally. The latter feature of DTD led to a decision to use ‘scope prefixes’ in XML output to avoid potential name conflicts. For example, consider the following ASN.1 specification:

Date ::= CHOICE {

str VisibleString,

std Date-std

}

Time ::= CHOICE {

str VisibleString,

std Time-std

}

Here, accidentally, element str is defined identically both in Date and Time productions; while the meaning of element std depends on the context. To avoid ambiguity, this specification translates into the following DTD:

<!ELEMENT Date (Date_str | Date_std)>

<!ELEMENT Date_str (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT Date_std (Date-std)>

<!ELEMENT Time (Time_str | Time_std)>

<!ELEMENT Time_str (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT Time_std (Time-std)>

Accordingly, these scope prefixes made their way into XML output.

Later, DTD parsing was added into DATATOOL. Here, scope prefixes were not needed. Also, since these prefixes considerably increase the size of the XML output, they could be omitted when it is known in advance that there can be no ambiguity. So, DATATOOL has got command line flags, which would enable that.

With the addition of XML Schema parser and generator, when converting ASN.1 specification, elements can be declared in Schema locally if needed, and scope prefixes make almost no sense. Still, they are preserved for compatibility.

Modular DTD and Schemata

Here, ‘module’ means ASN.1 module. Single ASN.1 specification file may contain several modules. When converting it into DTD or XML schema, it might be convenient to put each module definitions into a separate file. To do so, one should specify a special file name in -fx or -fxs command line parameter. The names of output DTD or Schema files will then be chosen automatically - they will be named after ASN.1 modules defined in the source. ‘Modular’ output does not make much sense when the source specification is DTD or Schema.

You can find a number of DTDs and Schema converted by DATATOOL from NCBI public ASN.1 specifications here.

Converting XML Schema into ASN.1

There are two major problems in converting XML schema into ASN.1 specification: how to define XML attributes and how to convert complex content models. The solution was greatly affected by the underlying implementation of data storage classes (classes which DATATOOL generates based on a specification). So, for example the following Schema

<xs:element name="Author">

<xs:complexType>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="LastName" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:choice minOccurs="0">

<xs:element name="ForeName" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="FirstName" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="MiddleName" type="xs:string" minOccurs="0"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:choice>

<xs:element name="Initials" type="xs:string" minOccurs="0"/>

<xs:element name="Suffix" type="xs:string" minOccurs="0"/>

</xs:sequence>

<xs:attribute name="gender" use="optional">

<xs:simpleType>

<xs:restriction base="xs:string">

<xs:enumeration value="male"/>

<xs:enumeration value="female"/>

</xs:restriction>

</xs:simpleType>

</xs:attribute>

</xs:complexType>

</xs:element>

translates into this ASN.1:

Author ::= SEQUENCE {

attlist SET {

gender ENUMERATED {

male (1),

female (2)

} OPTIONAL

},

lastName VisibleString,

fF CHOICE {

foreName VisibleString,

fM SEQUENCE {

firstName VisibleString,

middleName VisibleString OPTIONAL

}

} OPTIONAL,

initials VisibleString OPTIONAL,

suffix VisibleString OPTIONAL

}

Each unnamed local element gets a name. When generating C++ data storage classes from Schema, DATATOOL marks such data types as anonymous.

It is possible to convert source Schema into ASN.1, and then use DATATOOL to generate C++ classes from the latter. In this case DATATOOL and serial library provide compatibility of ASN.1 output. If you generate data storage classes from Schema, and use them to write data in ASN.1 format (binary or text), if you then convert that Schema into ASN.1, generate classes from it, and again write same data in ASN.1 format using this new set of classes, then these two files will be identical.

Definition File

It is possible to tune up the C++ code generation by using a definition file, which could be specified in the -od argument. The definition file uses the generic NCBI configuration format also used in the configuration (*.ini) files found in NCBI’s applications.

DATATOOL looks for code generation parameters in several sections of the file in the following order:

-

[ModuleName.TypeName]

-

[TypeName]

-

[ModuleName]

-

[-]

Parameter definitions follow a “name = value” format. The “name” part of the definition serves two functions: (1) selecting the specific element to which the definition applies, and (2) selecting the code generation parameter (such as _class) that will be fine-tuned for that element.

To modify a top-level element, use a definition line where the name part is simply the desired code generation parameter (such as _class). To modify a nested element, use a definition where the code generation parameter is prefixed by a dot-separated “path” of the successive container element names from the data format specification. For path elements of type SET OF or SEQUENCE OF, use an “E” as the element name (which would otherwise be anonymous). Note: Element names will depend on whether you are using ASN.1, DTD, or Schema.

For example, consider the following ASN.1 specification:

MyType ::= SEQUENCE {

label VisibleString ,

points SEQUENCE OF

SEQUENCE {

x INTEGER ,

y INTEGER

}

}

Code generation for the various elements can be fine-tuned as illustrated by the following sample definition file:

[MyModule.MyType]

; modify the top-level element (MyType)

_class = CMyTypeX

; modify a contained element

label._class = CTitle

; modify a "SEQUENCE OF" container type

points._type = vector

; modify members of an anonymous SEQUENCE contained in a "SEQUENCE OF"

points.E.x._type = double

points.E.y._type = double

; modify a DATATOOL-assigned class name

points.E._class = CPoint

Note: DATATOOL assigns arbitrary names to otherwise anonymous containers. In the example above, the SEQUENCE containing x and y has no name in the specification, so DATATOOL assigned the name E. If you want to change the name of a DATATOOL-assigned name, create a definition file and rename the class using the appropriate _class entry as shown above. To find out what the DATATOOL-assigned name will be, create a sample definition file using the DATATOOL -ods option. This approach will work regardless of the data specification format (ASN.1, DTD, or XSD).

The following additional topics are discussed in this section:

Common Definitions

Some definitions refer to the generated class as a whole.

_file Defines the base filename for the generated or referenced C++ class.

For example, the following definitions:

[ModuleName.TypeName]

_file=AnotherName

Or

[TypeName]

_file=AnotherName

would put the class CTypeName in files with the base name AnotherName, whereas these two:

[ModuleName]

_file=AnotherName

Or

put all the generated classes into a single file with the base name AnotherName.

_extra_headers Specify additional header files to include.

For example, the following definition:

[-]

_extra_headers=name1 name2 \"name3\"

would put the following lines into all generated headers:

#include <name1>

#include <name2>

#include "name3"

Note the name3 clause. Putting name3 in quotes instructs DATATOOL to use the quoted syntax in generated files. Also, the quotes must be escaped with backslashes.

_dir Subdirectory in which the generated C++ files will be stored (in case _file not specified) or a subdirectory in which the referenced class from an external module could be found. The subdirectory is added to include directives.

_class The name of the generated class (if _class=- is specified, then no code is generated for this type).

For example, the following definitions:

[ModuleName.TypeName]

_class=CAnotherName

Or

[TypeName]

_class=CAnotherName

would cause the class generated for the type TypeName to be named CAnotherName, whereas these two:

[ModuleName]

_class=CAnotherName

Or

would result in all the generated classes having the same name CAnotherName (which is probably not what you want).

_namespace The namespace in which the generated class (or classes) will be placed.

_parent_class The name of the base class from which the generated C++ class is derived.

_parent_type Derive the generated C++ class from the class, which corresponds to the specified type (in case _parent_class is not specified).

It is also possible to specify a storage-class modifier, which is required on Microsoft Windows to export/import generated classes from/to a DLL. This setting affects all generated classes in a module. An appropriate section of the definition file should look like this:

[-]

_export = EXPORT_SPECIFIER

Because this modifier could also be specified in the command line, the DATATOOL code generator uses the following rules to choose the proper one:

-

If no -oex flag is given in the command line, no modifier is added at all.

-

If -oex "" (that is, an empty modifier) is specified in the command line, then the modifier from the definition file will be used.

-

The command-line parameter in the form -oex FOOBAR will cause the generated classes to have a FOOBAR storage-class modifier, unless another one is specified in the definition file. The modifier from the definition file always takes precedence.

Definitions That Affect Specific Types

The following additional topics are discussed in this section:

INTEGER, REAL, BOOLEAN, NULL

_type C++ type: int, short, unsigned, long, etc.

ENUMERATED

_type C++ type: int, short, unsigned, long, etc.

_prefix Prefix for names of enum values. The default is “e”.

OCTET STRING

_char Vector element type: char, unsigned char, or signed char.

SEQUENCE OF, SET OF

_type STL container type: list, vector, set, or multiset.

SEQUENCE, SET

memberName._delay Mark the specified member for delayed reading.

CHOICE

_virtual_choice If not empty, do not generate a special class for choice. Rather make the choice class as the parent one of all its variants.

variantName._delay Mark the specified variant for delayed reading.

The Special [-] Section

There is a special section [-] allowed in the definition file which can contain definitions related to code generation. This is a good place to define a namespace or identify additional headers. It is a “top level” section, so entries placed here will override entries with the same name in other sections or on the command-line. For example, the following entries set the proper parameters for placing header files alongside source files:

[-]

; Do not use a namespace at all:

-on = -

; Use the current directory for generated .cpp files:

-opc = .

; Use the current directory for generated .hpp files:

-oph = .

; Do not add a prefix to generated file names:

-or = -

; Generate #include directives with quotes rather than angle brackets:

-orq = 1

Any of the code generation arguments in Table 2 (except -od, -odi, and -odw which are related to specifying the definition file) can be placed in the [-] section.

In some cases, the special value "-" causes special processing as noted in Table 2.

Examples

If we have the following ASN.1 specification (this not a “real” specification - it is only for illustration):

Date ::= CHOICE {

str VisibleString,

std Date-std

}

Date-std ::= SEQUENCE {

year INTEGER,

month INTEGER OPTIONAL

}

Dates ::= SEQUENCE OF Date

Int-fuzz ::= CHOICE {

p-m INTEGER,

range SEQUENCE {

max INTEGER,

min INTEGER

},

pct INTEGER,

lim ENUMERATED {

unk (0),

gt (1),

lt (2),

tr (3),

tl (4),

circle (5),

other (255)

},

alt SET OF INTEGER

}

Then the following definitions will effect the generation of objects:

| Definition |

Effected Objects |

[Date]

str._type = string |

the str member of the Date structure |

[Dates]

E._pointer = true |

elements of the Dates container |

[Int-fuzz]

range.min._type = long |

the min member of the range member of the Int-fuzz structure |

[Int-fuzz]

alt.E._type = long |

elements of the alt member of the Int-fuzz structure |

As another example, suppose you have a CatalogEntry type comprised of a Summary element and either a RecordA element or a RecordB element, as defined by the following XSD specification:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<schema

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema"

xmlns:tns="https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/some/unique/path"

targetNamespace="https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/some/unique/path"

elementFormDefault="qualified"

>

<element name="CatalogEntry" type="tns:CatalogEntryType" />

<complexType name="CatalogEntryType">

<sequence>

<element name="Summary" type="string" />

<choice>

<element name="RecordA" type="int" />

<element name="RecordB" type="int" />

</choice>

</sequence>

</complexType>

</schema>

In this specification, the <choice> element in CatalogEntryType is anonymous, so DATATOOL will assign an arbitrary name to it. The assigned name will not be descriptive, but fortunately you can use a definition file to change the assigned name.

First find the DATATOOL-assigned name by creating a sample definition file using the -ods option:

datatool -ods -oA -m catalogentry.xsd

The sample definition file (catalogentry._sample_def) shows RR as the class name:

[CatalogEntry]

RR._class =

Summary._class =

Then edit the module definition file (catalogentry.def) and change RR to a more descriptive class name, for example:

[CatalogEntry]

RR._class=CRecordChoice

The new name will be used the next time the module is built.

Module File

Module files are not used directly by DATATOOL, but they are read by new_module.sh and project_tree_builder and therefore determine what DATATOOL’s command line will be when DATATOOL is invoked from the NCBI build system.

Module files simply consist of lines of the form “KEY = VALUE”. Only the key MODULE_IMPORT is currently used (and is the only key ever recognized by project_tree_builder). Other keys used to be recognized by module.sh and still harmlessly remain in some files. The possible keys are:

-

MODULE_IMPORT These definitions contain a space-delimited list of other modules to import. The paths should be relative to .../src and should not include extensions.

For example, a valid entry could be:

MODULE_IMPORT = objects/general/general objects/seq/seq

-

MODULE_ASN, MODULE_DTD, MODULE_XSD These definitions explicitly set the specification filename (normally foo.asn, foo.dtd, or foo.xsd for foo.module). Almost no module files contain this definition. It is no longer used by the project_tree_builder and is therefore not necessary

-

MODULE_PATH Specifies the directory containing the current module, again relative to .../src. Almost all module files contain this definition, however it is no longer used by either new_module.sh or the project_tree_builder and is therefore not necessary.

Generated Code

The following additional topics are discussed in this section:

Normalized Name

By default, DATATOOL generates “normalized” C++ class names from ASN.1 type names using two rules:

-

Convert any hyphens (“-”) into underscores (“_”), because hyphens are not legal characters in C++ class names.

-

Prepend a ‘C’ character.

For example, the default normalized C++ class name for the ASN.1 type name “Seq-data” is “CSeq_data”.

The default C++ class name can be overridden by explicitly specifying in the definition file a name for a given ASN.1 type name. For example:

[MyModule.Seq-data]

_class=CMySeqData

ENUMERATED Types

By default, for every ENUMERATED ASN.1 type, DATATOOL will produce a C++ enum type with the name ENormalizedName.

Class Diagrams

The following topics are discussed in this section:

Specification Analysis

The following topics are discussed in this section:

ASN.1 Specification Analysis

See Figure 1.

- ASN.1 specification analysis.

DTD Specification Analysis

See Figure 2.

- DTD specification analysis.

Data Types

See CDataType.

Data Values

See Figure 3.

- Data values.

Code Generation

See Figure 4.

- Code generation.

Load Balancing

Note: For security reasons not all links in the public version of this document are accessible by the outside NCBI users.

The section covers the following topics:

-

The purpose of load balancing

-

All the separate components’ purpose, internal details, configuration

-

Communications between the components

-

Monitoring facilities

Overview

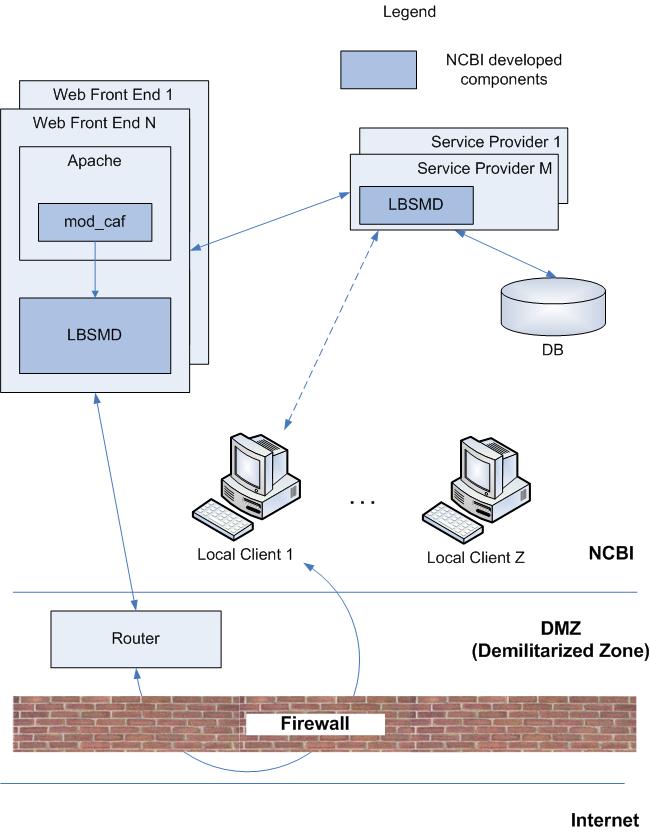

The purpose of load balancing is distributing the load among the service providers available on the NCBI network basing on certain rules. The load is generated by both locally-connected and Internet-connected users. The figures below show the most typical usage scenarios.

Figure 5. Local Clients

Please note that the figure is slightly simplified to remove unnecessary details for the time being.

In case of local access to the NCBI resources there are two NCBI developed components, which are involved into the interactions. These are LBSMD daemon (Load Balancing Service Mapping Daemon) and mod_caf (Cookie/Argument Affinity module) - an Apache web server module.

The LBSMD daemon is running on each host in the NCBI network. The daemon reads its configuration file with all the services available on the host described. Then the LBSMD daemon broadcasts the available services and the current host load to the adjacent LBSMD daemons on a regular basis. The data received from the other LBSMD daemons are stored in a special table. So at some stage the LBSMD daemon on each host will have had a full description of the services available on the network as well as the current hosts’ load.

The mod_caf Apache’s module analyses special cookies, query line arguments and reads data from the table populated by the LBSMD daemon. Basing on the best match it makes a decision of where to pass a request further.

Suppose for a moment that a local NCBI client runs a web browser, points to an NCBI web page and initiates a DB request via the web interface. At this stage the mod_caf analyses the request line and makes a decision where to pass the request. The request is passed to the ServiceProviderN host which performs the corresponding database query. Then the query results are delivered to the client. The data exchange path is shown on the figure above using solid lines.

Another typical scenario for the local NCBI clients is when client code is run on a user workstation. That client code might require a long term connection to a certain service, to a database for example. The browser is not able to provide this kind of connection so a direct connection is used in this case. The data exchange path is shown on the figure above using dashed lines.

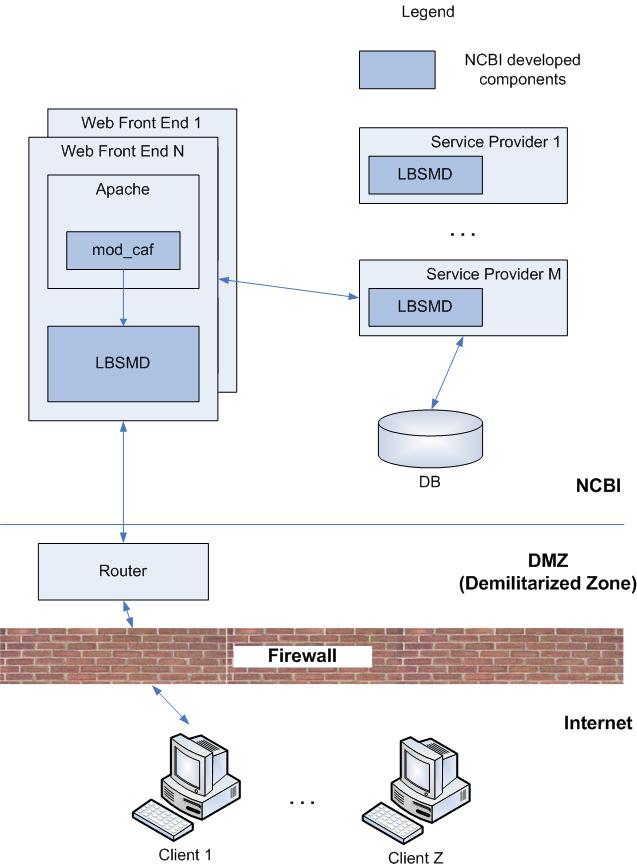

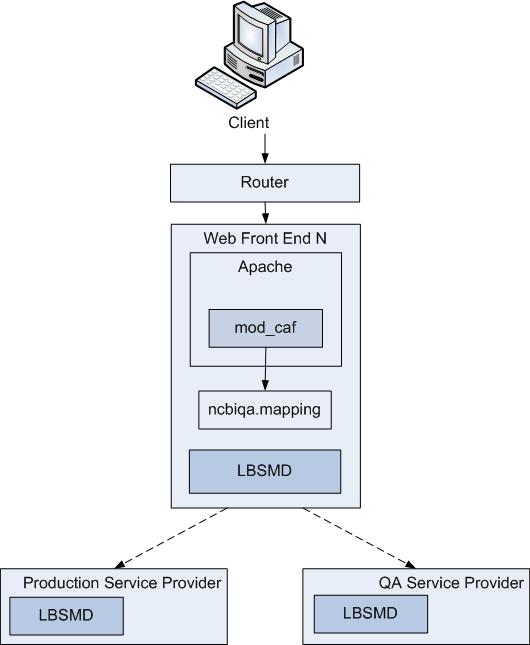

The communication scenarios become more complicated in case when clients are located outside of the NCBI network. The figure below describes the interactions between modules when the user requested a service which does not suppose a long term connection.

Figure 6. Internet Clients. Short Term Connection

The clients have no abilities to connect to front end Apache web servers directly. The connection is done via a router which is located in DMZ (Demilitarized Zone). The router selects one of the available front end servers and passes the request to that web server. Then the web server processes the request very similar to how it processes requests from a local client.

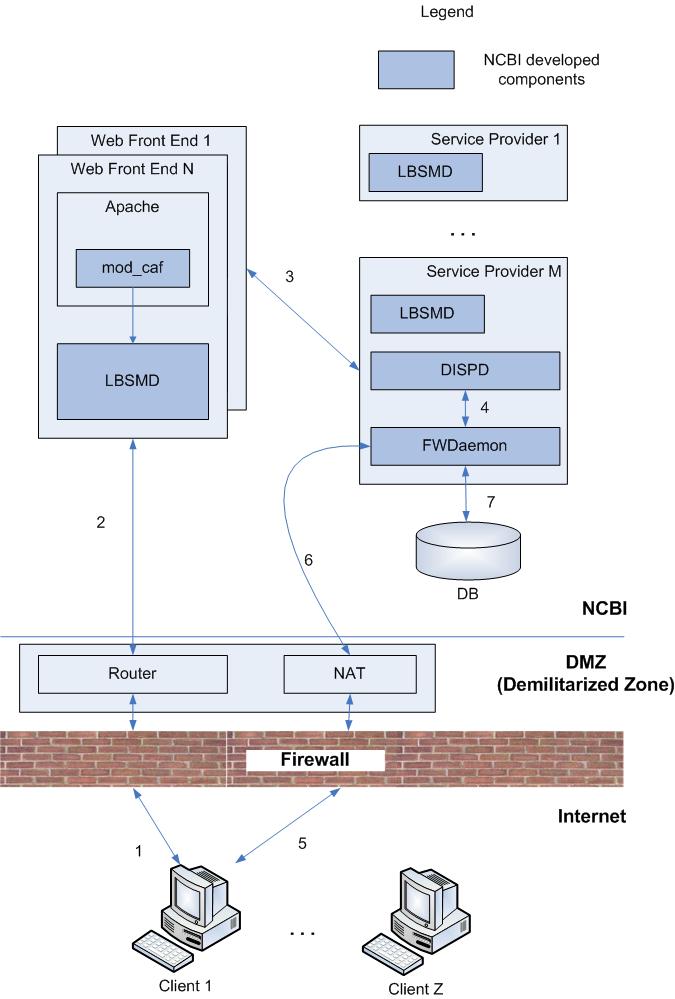

The next figure explains the interactions for the case when an Internet client requests a service which supposes a long term connection.

Figure 7. Internet Clients. Long Term Connection

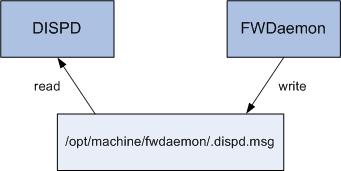

In opposite to the local clients the internet clients are unable to connect to the required service directly because of the DMZ zone. This is where DISPD, FWDaemon and a proxy come to help resolving the problem.

The data flow in the scenario is as follows. A request from the client reaches a front end Apache server as it was discussed above. Then the front end server passes the request to the DISPD dispatcher. The DISPD dispatcher communicates to FWDaemon (Firewall Daemon) to provide the required service facilities. The FWDaemon answers with a special ticket for the requested service. The ticket is sent to the client via the front end web server and the router. Then the client connects to the NAT service in the DMZ zone providing the received ticket. The NAT service establishes a connection to the FWDaemon and passes the received earlier ticket. The FWDaemon, in turn, provides the connection to the required service. It is worth to mention that the FWDaemon is running on the same host as the DISPD dispatcher and neither DISPD nor FWDaemon can work without each other.

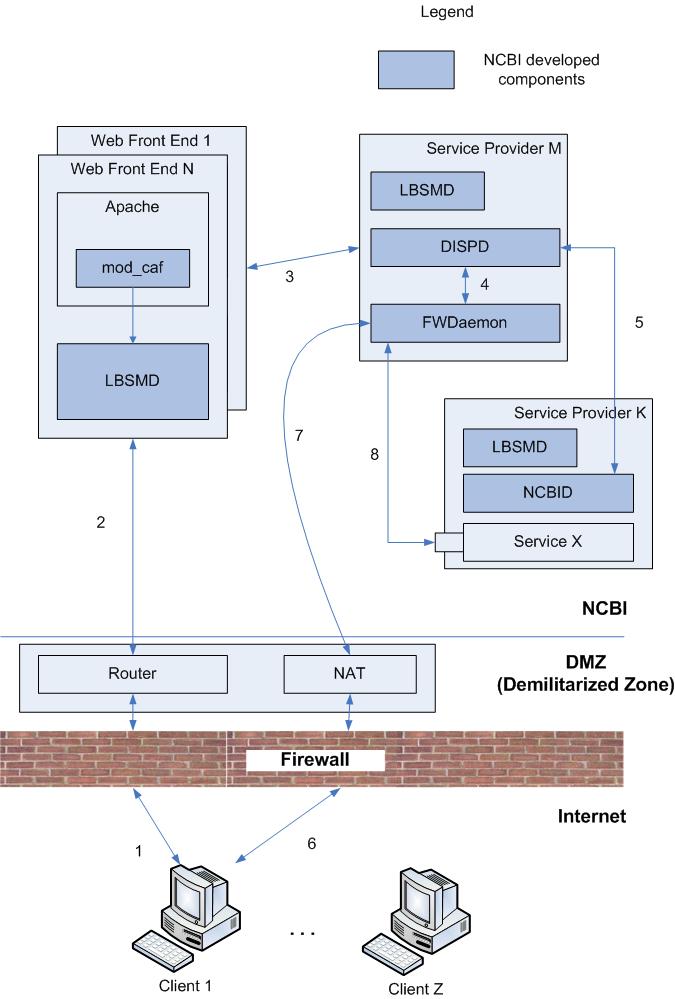

The most complicated scenario comes to the picture when an arbitrary Unix filter program is used as a service provided for the outside NCBI users. The figure below shows all the components involved into the scenario.

Figure 8. NCBID at Work

The data flow in the scenario is as follows. A request from the client reaches a front end Apache server as it was discussed above. Then the front end server passes the request to the DISPD dispatcher. The DISPD communicates to both the FWDaemon and the NCBID utility on (possibly) the other host and requests to demonize a requested Unix filter program (Service X on the figure). The demonized service starts listening on the certain port for a network connection. The connection attributes are delivered to the FWDaemon and to the client via the web front end and the router. The client connects to the NAT service and the NAT service passes the request further to the FWDaemon. The FWDaemon passes the request to the demonized Service X on the Service Provider K host. Since that moment the client is able to start data exchange with the service. The described scenario is purposed for long term connections oriented tasks.

Further sections describe all the components in more detail.

Load Balancing Service Mapping Daemon (LBSMD)

Overview

As mentioned earlier, the LBSMD daemon runs almost on every host that carries either public or private servers which, in turn, implement NCBI services. The services include CGI programs or standalone servers to access NCBI data.

Each service has a unique name assigned to it. The “TaxService” would be an example of such a name. The name not only identifies a service. It also implies a protocol which is used for data exchange with that service. For example, any client which connects to the “TaxService” service knows how to communicate with that service regardless the way the service is implemented. In other words the service could be implemented as a standalone server on host X and as a CGI program on the same host or on another host Y (please note, however, that there are exceptions and for some service types it is forbidden to have more than one service type on the same host).

A host can advertize many services. For example, one service (such as “Entrez2”) can operate with binary data only while another one (such as “Entrez2Text”) can operate with text data only. The distinction between those two services could be made by using a content type specifier in the LBSMD daemon configuration file.

The main purpose of the LBSMD daemon is to maintain a table of all services available at NCBI at the moment. In addition the LBSMD daemon keeps track of servers that are found to be dysfunctional (dead servers). The daemon is also responsible for propagating trouble reports, obtained from applications. The application trouble reports are based on their experience with advertised servers (e.g., an advertised server is not technically marked dead but generates some sort of garbage). Further in this document, the latter kind of feedback is called a penalty.

The principle of load balancing is simple: each server which implements a service is assigned a (calculated) rate. The higher the rate, the better the chance for that server to be chosen when a request for the service comes up. Note that load balancing is thus almost never deterministic.

The LBSMD daemon calculates two parameters for the host on which it is running. The parameters are a normal host status and a BLAST host status (based on the instant load of the system). These parameters are then used to calculate the rate of all (non static) servers on the host. The rates of all other hosts are not calculated but received and stored in the LBSMD table.

The LBSMD daemon can be restarted from a crontab every few minutes on all the production hosts to ensure that the daemon is always running. This technique is safe because no more than one instance of the daemon is permitted on a certain host and any attempt to start more than one is ignored. Normally, though, a running daemon instance is maintained afloat by some kind of monitoring software, such as “puppet” or “monit” that makes use of the crontabs unnecessary.

The main loop of the LBSMD daemon:

-

periodically checks the configuration file and reloads the configuration when necessary;

-

checks for and processes incoming messages from neighbor LBSMD daemons running on other hosts; and

-

generates and broadcasts the messages to the other hosts about the load of the system and configured services.

The LBSMD daemon can also periodically check whether the configured servers are alive: either by trying to establish a connection to them (and then disconnecting immediately, without sending/receiving any data) and / or by using a special plugin script that can do more intelligent, thorough, and server-specific diagnostics, and report the result back to LBSMD via an exit code.

Lastly, LBSMD can pull port load information as posted by the running servers. This is done via a simple API https://intranet.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/ToolBox/CPP_DOC/lxr/source/include/connect/daemons/lbsmdapi.h. The information is then used to calculate the final server rates in run-time.

Although cients can redirect services, LBSMD does not distinguish between direct and redirected services.

Configuration

The LBSMD daemon is configured via command line options and via a configuration file. The full list of command line options can be retrieved by issuing the following command:

/opt/machine/lbsm/sbin/lbsmd --help

The local NCBI users can also visit the following link:

https://intranet.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/ToolBox/NETWORK/lbsmd.cgi

The default name of the LBSMD daemon configuration file is /etc/lbsmd/servrc.cfg. Each line can be one of the following:

-

an include directive

-

site / zone designation

-

host authority information

-

a monitored port designation

-

a part of the host environment

-

a service definition

-

an empty line (entirely blank or containing a comment only)

Empty lines are ignored in the file. Any single configuration line can be split into several physical lines by inserting backslash symbols (\) before the line breaks. A comment is introduced by the pound/hash symbol (#).

A configuration line of the form

causes the contents of the named file filename to be inserted here. The daemon always assumes that relative file names (those that do not start with the slash character, /) are based on the daemon startup directory. This is true for any level of nesting.

Once started, the daemon first tries to read its configuration from /etc/lbsmd/servrc.cfg. If the file is not found (or is not readable) the daemon looks for the configuration file servrc.cfg in the directory from which it has been started. This fallback mechanism is not used when the configuration file name is explicitly stated in the command line. The daemon periodically checks the configuration file and all of its descendants and reloads (discards) their contents if some of the files have been either updated, (re-)moved, or added.

The “filename” can be followed by a pipe character ( | ) and some text (up to the end of the line or the comment introduced by the hash character). That text is then prepended to every line (but the %include directives) read from the included file.

A configuration line of the form

specifies the zone to which the entire configuration file applies, where a zone is a subdivision of the existing broadcast domain which does not intermix with other unrelated zones. Only one zone designation is allowed, and it must match the predefined site information (the numeric designation of the entire broadcast domain, which is either “guessed” by LBSMD or preset via a command-line parameter): the zone value must be a binary subset of the site value (which is usually a contiguous set of 1-bits, such as 0xC0 or 0x1E).

When no zone is specified, the zone is set equal to the entire site (broadcast domain) so that any regular service defined by the configuration is visible to each and every LBSMD running at the same site. Otherwise, only the servers with bitwise-matching zones are visible to each other: if 1, 2, and 3 are the zones of hosts “X”, “Y” and “Z”, respectively (all hosts reside within the same site, say 7), then servers from “X” are visible by “Z”, but not by “Y”; servers from “Y” are visible by “Z” but not by “X”; and finally, all servers from “Z” are visible by both “X” and “Y”. There’s a way to define servers at “X” to be visible by “Y” using an “Inter” server flag (see below).

A configuration line of the form

introduces a user that is added to the host authority. There can be multiple authority lines across the configuration, and they are all aggregated into a list. The list can contain both individual user names and / or group names (denoted by a preceding asterisk). The listed users and / or members of the listed groups, will be allowed to operate on all server records that appear in the LBSMD configuration files on this host (individual server entries may designate additional personnel on a per-server basis). Additional authority entries are only allowed from the same branch of the configuration file tree: so if a file “a” includes a file “b”, where the first host authority is defined, then any file that is included (directly or indirectly) from “b” can add entries to the host authority, while no other file that is included later from “a”, can.

A configuration line of the form

designates a local network port for monitoring by LBSMD: the daemon will regularly pull the port information as provided by servers in run-time: total port capacity, used capacity and free capacity; and make these values available in the load-balance messages sent to other LBSMDs. The ratio “free” over “total” will be used to calculate the port availability (1.0=fully free, 0.0=fully clogged). Servers may use arbitrary units to express the capacity, but both “used” and “free” may not be greater than “total”, and “used” must correspond to the actual used resource, yet “free” may be either calculated (e.g. algorithmically decreased in anticipation of the mouting load in order to shrink the port availability ratio quicker) or simply amounts to “total” – “used”. Note that “free” set to “0” signals the port as currently being unavailable for service (i.e. as if the port was down) – and an automatic connection check, if any, will not be performed by LBSMD on that port.

A configuration line of the form

goes into the host environment. The host environment can be accessed by clients when they perform the service name resolution. The host environment is designed to help the client to know about limitations/options that the host has, and based on this additional information the client can make a decision whether the server (despite the fact that it implements the service) is suitable for carrying out the client’s request. For example, the host environment can give the client an idea about what databases are available on the host. The host environment is not interpreted or used in any way by either the daemon or by the load balancing algorithm, except that the name must be a valid identifier. The value may be practically anything, even empty. It is left solely for the client to parse the environment and to look for the information of interest. The host environment can be obtained from the service iterator by a call to SERV_GetNextInfoEx() (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/IEB/ToolBox/CPP_DOC/lxr/ident?i=SERV_GetNextInfoEx), which is documented in the service mapping API

Note: White space characters which surround the name are not preserved but they are preserved in the value i.e. when they appear after the “=” sign.

A configuration line of the form

service_name [check_specifier] server_descriptor [| launcher_info ]

defines a server. The detailed description of the individual fields is given below.

-

service_name specifies the service name that the server is part of, for example TaxService. The same service_name may be used in multiple server definition lines to add more servers implementing that service.

-

[check_specifier] is an optional parameter (if omitted, the surrounding square brackets must not be used). The parameter is a comma separated list and each element in the list can be one of the following.

-

[-]N[/M] where N and M are integers. This will lead to checking every N seconds with backoff time of M seconds if failed. The “-“ character is used when it is required to check dependencies only, but not the primary connection point. “0”, which stands for “no check interval”, disables checks for the service.

-

[!][host[:port]][+[service]] which describes a dependency. The “!” character means negation. The service is a service name the describing service depends on and runs on host:port. The pair host:port is required if no service is specified. The host, :port, or both can be missing if service is specified (in that case the missing parts are read as “any”). The “+” character alone means “this service’s name” (of the one currently being defined). Multiple dependency specifications are allowed.

-

[~][DOW[-DOW]][@H[-H]] which defines a schedule. The “~” character means negation. The service runs from DOW to DOW (DOW is one of Su, Mo, Tu, We, Th, Fr, Sa, or Hd, which stands for a federal holiday, and cannot be used in weekday ranges) or any if not specified, and between hours H to H (9-5 means 9:00am thru 4:59pm, 18-0 means 6pm thru midnight). Single DOW and / or H are allowed and mean the exact day of week (or a holiday) and / or one exact hour. Multiple schedule specifications are allowed.

-

email@ncbi.nlm.nih.gov which makes the LBSMD daemon to send an e-mail to the specified address whenever this server changes its status (e.g. from up to down). Multiple e-mail specifications are allowed. The ncbi.nlm.nih.gov part is fixed and may not be changed.

-

user or *group which makes the LBSMD daemon add the specified user or group of users to the list of personnel who are authorized to modify the server (e.g. post a penalty, issue a rerate command etc.). By default these actions are only allowed to the root and lbsmd users, as well as users added to the host authority. Multiple specifications are allowed.

-

script which specifies a path to a local executable which checks whether the server is operational. The LBSMD daemon starts this script periodically as specified by the check time parameter(s) above. Only a single script specification is allowed. See Check Script Specification for more details.

-

server_descriptor specifies the address of the server and supplies additional information. An example of the server_descriptor:

STANDALONE somehost:1234 R=3000 L=yes S=yes B=-20

See Server Descriptor Specification for more details.

-

launcher_info is basically a command line preceded by a pipe symbol ( | ) which plays a role of a delimiter from the server_descriptor. It is only required for the NCBID type of service which are configured on the local host.

Check Script Specification

The check script file is configured between square brackets ‘[’ and ‘]’ in the service definition line. For example, the service definition line:

MYSERVICE [5, /bin/user/directory/script.sh] STANDALONE :2222 ...

sets the period in seconds between script checks as “5” (the default period is 15 seconds) and designates the check script file as “/bin/user/directory/script.sh” to be launched every 5 seconds. You can prefix the period with a minus sign (-) to indicate that LBSMD should not check the connection point (:2222 in this example) on its own, but should only run the script. The script must finish before the next check run is due. Otherwise, LBSMD will kill the script and ignore the result. Multiple repetitive failures may result in the check script removal from the check schedule.

The following command-line parameters are always passed to the script upon execution:

-

argv[0] = name of the executable with preceding ‘|’ character if stdin / stdout are open to the server connection (/dev/null otherwise), NB: ‘|’ is not always readily accessible from within shell scripts, so it’s duplicated in argv[2] for convenience;

-

argv[1] = name of the service being checked;

-

argv[2] = if piped, “|host:port” of the connection point being checked, otherwise “host:port” of the server as per configuration;

The following additional command-line parameters will be passed to the script if it has been run before:

-

argv[3] = exit code obtained in the last check script run;

-

argv[4] = repetition count for argv[3] (NB: 0 means this is the first occurrence of the exit code given in argv[3]);

-

argv[5] = seconds elapsed since the last check script run.

Output to stderr is attached to the LBSMD log file; the CPU limit is set to maximal allowed execution time. Nevertheless, the check must finish before the next invocation is due, per the server configuration.

The check script is expected to produce one of the following exit codes:

| Code(s) |

Meaning |

| 0 |

The server is fully available, i.e. “running at full throttle”. |

| 1 - 99 |

Indicates the approximate percent of base capacity used. |

| 100 - 110 |

Server state is set as RESERVED. RESERVED servers are unavailable to most clients but not considered as officially DOWN. |

| 111 - 120 |

The server is not available and must not be used, i.e. DOWN. |

| 123 |

Retain the previous exit code (as supplied in argv[3]) and increment the repetition count. Retain the current server state, otherwise, and log a warning. |

| 124 (not followed by 125) |

Retain the current server state. |

| 124 followed by 125 |

Turn the server off, with no more checks. Note: This only applies when 124 is followed by 125, both without repetitions. |

| 125 (not preceded by 124) |

Retain the current server state. |

| 126 |

Script was found but not executable (POSIX, script error). |

| 127 |

Script was not found (POSIX, script error). |

| 200 - 210 |

STANDBY server (set the rate to 0.005). The rate will be rolled back to the previously set “regular” rate the next time the RERATE command comes; or when the check script returns anything other than 123, 124, 125, or the state-retaining ALERTs (211-220).

STANDBY servers are those having base rate in the range [0.001..0.009], with higher rates having better chance to get drafted for service. STANDBY servers are only used by clients if there are no usable non-STANDBY counterparts found. |

| 211 - 220 |

ALERT (email contacts and retain the current server state). |

| 221 - 230 |

ALERT (email contacts and base the server rate on the dependency check only). |

Exit codes 126, 127, and other unlisted codes are treated as if 0 had been returned (i.e. the server rate is based on the dependency check only).

Any exit code other than 123 resets the repetition count, even though the new code may be equal to the previous one. In the absence of a previous code, exit code 123 will not be counted as a repetition, will cause a warning to be logged.

Any exit code not from the table above will cause a warning to be logged, and will be treated as if 0 has been returned. Note that upon the exit code sequence 124,125 no further script runs will occur, and the server will be taken out of service.

If the check script crashes ungracefully (with or without the coredump) 100+ times in a row, it will be eliminated from further checks, and the server will be considered fully available (i.e. as if 0 had been returned).

Servers are called SUPPRESSED when they are 100% penalized (see server penalties below); while RESERVED is a special state that LBSMD maintains. 100% penalty makes an entry not only unavailable for regular use (same as RESERVED) but also assumes some maintenance work in progress (so that any underlying state changes will not be announced immediately but only when the entry goes out of the 100% penalized state, if any state change still remains). On the other hand and from the client perspective, RESERVED and SUPPRESSED may look identical.

Note: The check script operation is complementary to setting a penalty prior to doing any disruptive changes in production. In other words, the script is only reliable as long as the service is expected to work. If there is any scheduled maintenance, it should be communicated to LBSMD via a penalty rather than by an assumption that the failing script will do the job of bringing the service to the down state and excluding it from LB.

Server Descriptor Specification

The server_descriptor, also detailed in connect/ncbi_server_info.h (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/IEB/ToolBox/CPP_DOC/lxr/source/include/connect/ncbi_server_info.h), consists of the following fields:

server_type [host][:port] [arguments] [flags]

where:

-

server_type is one of the following keywords (more info):

-

NCBID for servers launched by ncbid.cgi

-

STANDALONE for standalone servers listening to incoming connections on dedicated ports

-

HTTP_GET for servers, which are the CGI programs accepting only the GET request method

-

HTTP_POST for servers, which are the CGI programs accepting only the POST request method

-

HTTP for servers, which are the CGI programs accepting either GET or POST request methods

-

DNS for introduction of a name (fake service), which can be used later in load-balancing for domain name resolution

-

NAMEHOLD for declaration of service names that cannot be defined in any other configuration files except for the current configuration file. Note: The FIREWALL server specification may not be used in a configuration file (i.e., may neither be declared as services nor as service name holders).

-

both host and port parameters are optional. Defaults are local host and port 80, except for STANDALONE and DNS servers, which do not have a default port value. If host is specified (by either of the following: keyword localhost, localhost IP address 127.0.0.1, real host name, or IP address) then the described server is not a subject for variable load balancing but is a static server. Such server always has a constant rate, independent of any host load.

-

arguments are required for HTTP* servers and must specify the local part of the URL of the CGI program and, optionally, parameters such as /somepath/somecgi.cgi?param1¶m2=value2¶m3=value3. If no parameters are to be supplied, then the question mark (?) must be omitted, too. For NCBID servers, arguments are parameters to pass to the server and are formed as arguments for CGI programs, i.e., param1¶m2¶m3=value. As a special rule, ‘’ (two single quotes) may be used to denote an empty argument for the NCBID server. STANDALONE and DNS servers do not take any arguments.

-

flags can come in any order (but no more than one instance of a flag is allowed) and essentially are the optional modifiers of values used by default. The following flags are recognized (see ncbi_server_info.h):

-

load calculation keyword:

-

Blast to use special algorithm for rate calculation acceptable for BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi) applications. The algorithm uses instant values of the host load and thus is less conservative and more reactive than the ordinary one.

-

Regular to use an ordinary rate calculation (default, and the only load calculation option allowed for static servers).

-

Either of these keywords may be suffixed with “Inter”, such as to form RegularInter, making the entry to cross the current zone boundary, and being available outside its zone.

-

base rate:

- R=value sets the base server reachability rate (as a floating point number); the default is 1000. Any negative value makes the server unreachable, and a value 0 means to use the default (which is 1000). The range of the base rate is between 0.001 and 100000. Note that the range [0.001—0.009] is reverved for STANDBY servers – the ones that are only used by clients if no other usable non-STANDBY counterparts can be found.

-

locality markers (Note: If necessary, both L and P markers can be combined in a particular service definition):

-

L={yes|no} sets (if yes) the server to be local only. The default is no. The service mapping API returns local only servers in the case of mapping with the use of LBSMD running on the same - local - host (direct mapping), or if the dispatching (indirect mapping) occurs within the NCBI Intranet. Otherwise, if the service mapping occurs using a non-local network (certainly indirectly, by exchange with dispd.cgi) then servers that are local only are not seen.

-

P={yes|no} sets (if yes) the server to be private. The default is no. Private servers are not seen by the outside NCBI users (exactly like local servers), but in addition these servers are not seen from the NCBI Intranet if requested from a host, which is different from one where the private server runs. This flag cannot be used for DNS servers.

-

Stateful server:

- S={yes|no}. The default is no.

Indication of stateful server, which allows only dedicated socket (stateful) connections. This tag is not allowed for HTTP* and DNS servers.

-

Secure server:

- $={yes|no}. The default is no.

Indication of the server to be used with secure connections only. For STANDALONE servers it means to use SSL, and for the HTTP* ones – to use the HTTPS protocol.

-

Content type indication:

- C=type/subtype [no default]

specification of Content-Type (including encoding), which server accepts. The value of this flag gets added automatically to any HTTP packet sent to the server by SERVICE connector. However, in order to communicate, a client still has to know and generate the data type accepted by the server, i.e. a protocol, which server understands. This flag just helps insure that HTTP packets all get proper content type, defined at service configuration. This tag is not allowed in DNS server specifications.

-

Bonus coefficient:

- B=double [0.0 = default]

specifies a multiplicative bonus given to a server run locally, when calculating reachability rate. Special rules apply to negative/zero values: 0.0 means not to use the described rate increase at all (default rate calculation is used, which only slightly increases rates of locally run servers). Negative value denotes that locally run server should be taken in first place, regardless of its rate, if that rate is larger than percent of expressed by the absolute value of this coefficient of the average rate coefficient of other servers for the same service. That is -5 instructs to ignore locally run server if its status is less than 5% of average status of remaining servers for the same service.

-

Validity period:

- T=integer [0 = default]

specifies the time in seconds this server entry is valid without update. (If equal to 0 then defaulted by the LBSM Daemon to some reasonable value.)

Server descriptors of type NAMEHOLD are special. As arguments, they have only a server type keyword. The namehold specification informs the daemon that the service of this name and type is not to be defined later in any configuration file except for the current one. Also, if the host (and/or port) is specified, then this protection works only for the service name on the particular host (and/or port).

Note: it is recommended that a dummy port number (such as :0) is always put in the namehold specifications to avoid ambiguities with treating the server type as a host name. The following example disables TestService of type DNS from being defined in all other configuration files included later, and TestService2 to be defined as a NCBID service on host foo:

TestService NAMEHOLD :0 DNS

TestService2 NAMEHOLD foo:0 NCBID

Sites

LBSMD is minimally aware of NCBI network layout and can generally guess its “site” information from either an IP address or special location-role files located in the /etc/ncbi directory: a BE-MD production and development site, a BE-MD.QA site, a BE-MD.TRY site, and lastly an ST-VA site. When reading zone information from the “@” directive of the configuration, LBSMD can treat special non-numeric values as the following: “@try” as the production zone within BE-MD.TRY, “@qa” as the production zone within BE-MD.QA, “@dev” as a development zone within the current site, and “@*prod*” (e.g. @intprod) as a production zone within the current site – where the production zone has a value of “1” and the development – “2”: so “@2” and “@dev” as well as “@1” and “@*prod*” are each equivalent. That makes the definition of zones more convenient by the %include directive with the pipe character:

%include /etc/ncbi/role |@ # define zone via the role file

Suppose that the daemon detected its site as ST-VA and assigned it a value of 0x300; then the above directive assigns the current zone the value of 0x100 if the file reads “prod” or “1”, and zone 0x200 if the file reads “dev” or “2”. Note that if the file reads either “try” or “qa”, or “4”, the implied “@” directive will flag an error because of the mismatch between the resultant zone and the current site values.

Both zone and site (or site alone) can be permanently assigned with the command-line parameters and then may not be overridden from the configuration file(s).

Signals

The table below describes the LBSMD daemon signal processing.

| Signal |

Reaction |

| SIGHUP |

reload the configuration |

| SIGINT |

quit |

| SIGTERM |

quit |

| SIGUSR1 |

toggle the verbosity level between less verbose (default) and more verbose (when every warning generated is stored) modes |

Automatic Configuration Distribution

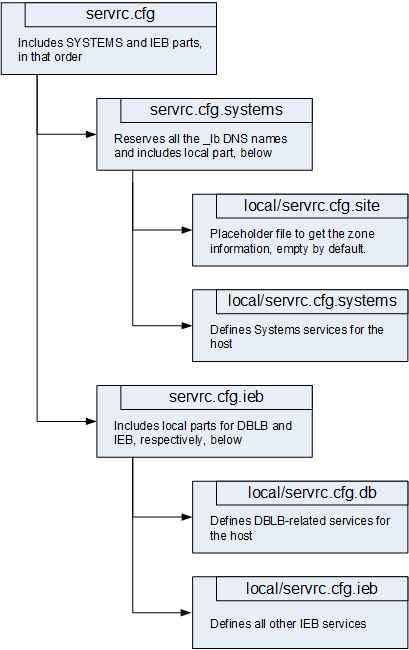

The configuration files structure is unified for all the hosts in the NCBI network. It is shown on the figure below.

Figure 9. LBSMD Configuration Files Structure

The common for all the configuration file prefix /etc/lbsmd is omitted on the figure. The arrows on the diagram show how the files are included.

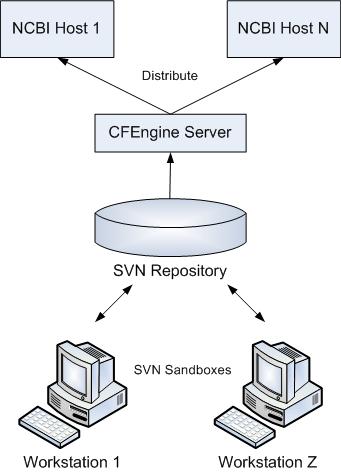

The files servrc.cfg and servrc.cfg.systems have fixed structure and should not be changed at all. The purpose of the file local/servrc.cfg.systems is to be modified by the systems group while the purpose of the file local/servrc.cfg.ieb is to be modified by the delegated members of the respected groups. To make it easier for changes all the local/servrc.cfg.ieb files from all the hosts in the NCBI network are stored in a centralized SVN repository. The repository can be received by issuing the following command:

svn co svn+ssh://subvert.be-md.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/export/home/LBSMD_REPO

The file names in that repository match the following pattern:

hostname.{be-md|st-va}[.qa]

where be-md is used for Bethesda, MD site and st-va is used for Sterling, VA site. The optional .qa suffix is used for quality assurance department hosts.

So, if it is required to change the /etc/lbsmd/local/servrc.cfg.ieb file on the sutils1 host in Bethesda the sutils1.be-md file is to be changed in the repository.

As soon as the modified file is checked in the file will be delivered to the corresponding host with the proper name automatically. The changes will take effect in a few minutes. The process of the configuration distribution is illustrated on the figure below.

Figure 10. Automatic Configuration Distribution

Monitoring and Control

Service Search

The following web page can be used to search for a service:

https://intranet.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/ToolBox/NETWORK/lbsmc/search.cgi

The following screen will appear

Figure 11. NCBI Service Search Page

As an example of usage a user might enter the partial name of the service like “TaxService” and click on the “Go” button. The search results will display “TaxService”, “TaxService3” and “TaxService3Test” if those services are available (see https://intranet.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/ToolBox/NETWORK/lbsmc/search.cgi?key=rb_svc&service=TaxService&host=&button=Go&db=).

lbsmc Utility

Another way of monitoring the LBSMD daemon is using the lbsmc (https://intranet.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/ToolBox/CPP_DOC/lxr/source/src/connect/daemons/lbsmc.c) utility. The utility periodically dumps onto the screen a table which represents the current content of the LBSMD daemon table. The utility output can be controlled by a number of command line options. The full list of available options and their description can be obtained by issuing the following command:

lbsmc -h

The NCBI intranet users can also get the list of options by clicking on this link: https://intranet.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/ToolBox/NETWORK/lbsmc.cgi?-h.

For example, to print a list of hosts which names match the pattern “sutil*” the user can issue the following command:

>./lbsmc -h sutil* 0

LBSMC - Load Balancing Service Mapping Client R100432

03/13/08 16:20:23 ====== widget3.be-md.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (00:00) ======= [2] V1.2

Hostname/IPaddr Task/CPU LoadAv LoadBl Joined Status StatBl

sutils1 151/4 0.06 0.03 03/12 13:04 397.62 3973.51

sutils2 145/4 0.17 0.03 03/12 13:04 155.95 3972.41

sutils3 150/4 0.20 0.03 03/12 13:04 129.03 3973.33

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Service T Type Hostname/IPaddr:Port LFS B.Rate Coef Rating

bounce +25 NCBID sutils1:80 L 1000.00 397.62

bounce +25 HTTP sutils1:80 1000.00 397.62

bounce +25 NCBID sutils2:80 L 1000.00 155.95

bounce +25 HTTP sutils2:80 1000.00 155.95

bounce +27 NCBID sutils3:80 L 1000.00 129.03

bounce +27 HTTP sutils3:80 1000.00 129.03

dispatcher_lb 25 DNS sutils1:80 1000.00 397.62

dispatcher_lb 25 DNS sutils2:80 1000.00 155.95

dispatcher_lb 27 DNS sutils3:80 1000.00 129.03

MapViewEntrez 25 STANDALONE sutils1:44616 L S 1000.00 397.62

MapViewEntrez 25 STANDALONE sutils2:44616 L S 1000.00 155.95

MapViewEntrez 27 STANDALONE sutils3:44616 L S 1000.00 129.03

MapViewMeta 25 STANDALONE sutils2:44414 L S 0.00 0.00

MapViewMeta 27 STANDALONE sutils3:44414 L S 0.00 0.00

MapViewMeta 25 STANDALONE sutils1:44414 L S 0.00 0.00

sutils_lb 25 DNS sutils1:80 1000.00 397.62

sutils_lb 25 DNS sutils2:80 1000.00 155.95

sutils_lb 27 DNS sutils3:80 1000.00 129.03

TaxService 25 NCBID sutils1:80 1000.00 397.62

TaxService 25 NCBID sutils2:80 1000.00 155.95

TaxService 27 NCBID sutils3:80 1000.00 129.03

TaxService3 +25 HTTP_POST sutils1:80 1000.00 397.62

TaxService3 +25 HTTP_POST sutils2:80 1000.00 155.95

TaxService3 +27 HTTP_POST sutils3:80 1000.00 129.03

test +25 HTTP sutils1:80 1000.00 397.62

test +25 HTTP sutils2:80 1000.00 155.95

test +27 HTTP sutils3:80 1000.00 129.03

testgenomes_lb 25 DNS sutils1:2441 1000.00 397.62

testgenomes_lb 25 DNS sutils2:2441 1000.00 155.95

testgenomes_lb 27 DNS sutils3:2441 1000.00 129.03

testsutils_lb 25 DNS sutils1:2441 1000.00 397.62

testsutils_lb 25 DNS sutils2:2441 1000.00 155.95

testsutils_lb 27 DNS sutils3:2441 1000.00 129.03

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* Hosts:4\747, Srvrs:44/1223/23 | Heap:249856, used:237291/249616, free:240 *

LBSMD PID: 17530, config: /etc/lbsmd/servrc.cfg

NCBI Intranet Web Utilities

The NCBI intranet users can also visit the following quick reference links:

If the lbsmc utility is run with the -f option then the output contains two parts:

The output is provided in either long or short format. The format depends on whether the -w option was specified in the command line (the option requests the long (wide) output). The wide output occupies about 132 columns, while the short (normal) output occupies only 80, which is the standard terminal width.

In case if the service name is more than the allowed number of characters to display the trailing characters will be replaced with “>”. When there is more information about the host / service to be displayed the “+” character is put beside the host / service name (this additional information can be retrieved by adding the -i option). When both “+” and “>” are to be shown they are replaced with the single character “*”. In the case of wide-output format the “#” character shown in the service line means that there is no host information available for the service (similar to the static servers). The “!” character in the service line denotes that the service was configured / stored with an error (this character actually should never appear in the listings and should be reported whenever encountered). Wide output for hosts contains the time of bootup and startup. If the startup time is preceded by the “~” character then the host was gone for a while and then came back while the lbsmc utility was running. The “+” character in the times is to show that the date belongs to the past year(s).

Server Penalizer API and Utility

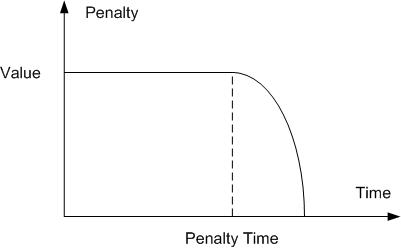

The utility allows to report problems of accessing a certain server to the LBSMD daemon, in the form of a penalty which is a value in the range [0..100] that shows, in percentages, how bad the server is. The value 0 means that the server is completely okay, whereas 100 means that the server (is misbehaving and) should not be used at all. The penalty is not a constant value: once set, it starts to decrease in time, at first slowly, then faster and faster until it reaches zero. This way, if a server was penalized for some reason and later the problem has been resolved, then the server becomes available gradually as its penalty (not being reset by applications again in the absence of the offending reason) becomes zero. The figure below illustrates how the value of penalty behaves.

Figure 12. Penalty Value Characteristics

Technically, the penalty is maintained by a daemon, which has the server configured, i.e., received by a certain host, which may be different from the one where the server was put into the configuration file. The penalty first migrates to that host, and then the daemon on that host announces that the server was penalized.

Note: Once a daemon is restarted, the penalty information is lost.

Service mapping API has a call SERV_Penalize() (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/IEB/ToolBox/CPP_DOC/lxr/ident?i=SERV_Penalize) declared in connect/ncbi_service.h (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/IEB/ToolBox/CPP_DOC/lxr/source/include/connect/ncbi_service.h), which can be used to set the penalty for the last server obtained from the mapping iterator.

For script files (similar to the ones used to start/stop servers), there is a dedicated utility program called lbsm_feedback (https://intranet.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/ToolBox/CPP_DOC/lxr/source/src/connect/daemons/lbsm_feedback.c), which sets the penalty from the command line. This command should be used with extreme care because it affects the load-balancing mechanism substantially,.

lbsm_feedback is a part of the LBSM set of tools installed on all hosts which run LBSMD. As it was explained above, penalizing means to make a server less favorable as a choice of the load balancing mechanism. Because of the fact that the full penalty of 100% makes a server unavailable for clients completely, at the time when the server is about to shut down (restart), it is wise to increase the server penalty to the maximal value, i.e. to exclude the server from the service mapping. (Otherwise, the LBSMD daemon might not immediately notice that the server is down and may continue dispatching to that server.) Usually, the penalty takes at most 5 seconds to propagate to all participating network hosts. Before an actual server shutdown, the following sequence of commands can be used:

> /opt/machine/lbsm/sbin/lbsm_feedback 'Servicename STANDALONE host 100 120'

> sleep 5

now you can shutdown the server

The effect of the above is to set the maximal penalty 100 for the service Servicename (of type STANDALONE) running on host host for at least 120 seconds. After 120 seconds the penalty value will start going down steadily and at some stage the penalty becomes 0. The default hold time equals 0. It takes some time to deliver the penalty value to the other hosts on the network so ‘sleep 5’ is used. Please note the single quotes surrounding the penalty specification: they are required in a command shell because lbsm_feedback takes only one argument which is the entire penalty specification.

As soon as the server is down, the LBSMD daemon detects it in a matter of several seconds (if not instructed otherwise by the configuration file) and then does not dispatch to the server until it is back up. In some circumstances, the following command may come in handy:

> /opt/machine/lbsm/sbin/lbsm_feedback 'Servicename STANDALONE host 0'

The command resets the penalty to 0 (no penalty) and is useful when, as for the previous example, the server is restarted and ready in less than 120 seconds, but the penalty is still held high by the LBSMD daemon on the other hosts.

The formal description of the lbsm_feedback utility parameters is given below.

Figure 13. lbsm_feedback Arguments

The servicename can be an identifier with ‘*’ for any symbols and / or ‘?’ for a single character. The penalty value is an integer value in the range 0 … 100. The port number and time are integers. The hostname is an identifier and the rate value is a floating point value.

SVN Repository

The SVN repository where the LBSMD daemon source code is located can be retrieved by issuing the following command:

svn co https://svn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/repos/toolkit/trunk/c++

The daemon code is in this file:

c++/src/connect/daemons/lbsmd.c

Log Files

The LBSMD daemon stores its log files at the following location:

/var/log/lbsmd

The file is formed locally on a host where LBSMD daemon is running. The log file size is limited to prevent the disk being flooded with messages. A standard log rotation is applied to the log file so you may see the files:

/var/log/lbsmd.X.gz

where X is a number of the previous log file.

The log file size can be controlled by the -s command line option. By default, -s 0 is the active flag, which provides a way to create (if necessary) and to append messages to the log file with no limitation on the file size whatsoever. The -s -1 switch instructs indefinite appending to the log file, which must exist. Otherwise, log messages are not stored. -s positive_number restricts the ability to create (if necessary) and to append to the log file until the file reaches the specified size in kilobytes. After that, message logging is suspended, and subsequent messages are discarded. Note that the limiting file size is only approximate, and sometimes the log file can grow slightly bigger. The daemon keeps track of log files and leaves a final logging message, either when switching from one file to another, in case the file has been moved or removed, or when the file size has reached its limit.

NCBI intranet users can get few (no more than 100) recent lines of the log file on an NCBI internal host. It is also possible to visit the following link:

https://intranet.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ieb/ToolBox/NETWORK/lbsmd.cgi?log

Configuration Examples

Here is an example of a LBSMD configuration file:

# $Id$

#

# This is a configuration file of new NCBI service dispatcher

#

#

# DBLB interface definitions

%include /etc/lbsmd/servrc.cfg.db

# IEB's services

testHTTP /Service/test.cgi?Welcome L=no

Entrez2[0] HTTP_POST www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /entrez/eutils/entrez2server.fcgi \

C=x-ncbi-data/x-asn-binary L=no

Entrez2BLAST[0] HTTP_POST www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /entrez/eutils/entrez2server.cgi \

C=x-ncbi-data/x-asn-binary L=yes

CddSearch [0] HTTP_POST www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /Structure/cdd/c_wrpsb.cgi \

C=application/x-www-form-urlencoded L=no

CddSearch2 [0] HTTP_POST www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi \

C=application/x-www-form-urlencoded L=no

StrucFetch [0] HTTP_POST www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /Structure/mmdb/mmdbsrv.cgi \

C=application/x-www-form-urlencoded L=no

bounce[60]HTTP /Service/bounce.cgi L=no C=x-ncbi-data/x-unknown

# Services of old dispatcher

bounce[60]NCBID '' L=yes C=x-ncbi-data/x-unknown | \

..../web/public/htdocs/Service/bounce

Database Load Balancing

Database load balancing is an important part of the overall load balancing function. Please see the Database Load Balancer section in the Database Access chapter for more details.

DISPD Network Dispatcher

Overview

The DISPD dispatcher is a CGI/1.0-compliant program (the actual file name is dispd.cgi). Its purpose is mapping a requested service name to an actual server location when the client has no direct access to the LBSMD daemon. This mapping is called dispatching. Optionally, the DISPD dispatcher can also pass data between the client, who requested the mapping, and the server, which implements the service, found as a result of dispatching. This combined mode is called a connection. The client may choose any of these modes if there are no special requirements on data transfer (e.g., firewall connection). In some cases, however, the requested connection mode implicitly limits the request to be a dispatching-only request, and the actual data flow between the client and the server occurs separately at a later stage.

Protocol Description

The dispatching protocol is designed as an extension of HTTP/1.0 and is coded in the HTTP header parts of packets. The request (both dispatching and connection) is done by sending an HTTP packet to the DISPD dispatcher with a query line of the form:

which can be followed by parameters (if applicable) to be passed to the service. The <name> defines the name of the service to be used. The other parameters take the form of one or more of the following constructs:

where square brackets are used to denote an optional value part of the parameter.

In case of a connection request the request body can contain data to be passed to the first-found server. A connection to this server is automatically initiated by the DISPD dispatcher. On the contrary, in case of a dispatching-only request, the body is completely ignored, that is, the connection is dropped after the header has been read and then the reply is generated without consuming the body data. That process may confuse an unprepared client.

Mapping of a service name into a server address is done by the LBSMD daemon which is run on the same host where the DISPD dispatcher is run. The DISPD dispatcher never dispatches a non-local client to a server marked as local-only (by means of L=yes in the configuration of the LBSMD daemon). Otherwise, the result of dispatching is exactly what the client would get from the service mapping API if run locally. Specifying capabilities explicitly the client can narrow the server search, for example, by choosing stateless servers only.

Client Request to DISPD

The following additional HTTP tags are recognized in the client request to the DISPD dispatcher.

| Tag |

Description |

Accepted-Server-Types: <list> |

The <list> can include one or more of the following keywords separated by spaces:

NCBID STANDALONE HTTP HTTP_GET HTTP_POST FIREWALL

The keyword describes the server type which the client is capable to handle. The default is any (when the tag is not present in the HTTP header), and in case of a connection request, the dispatcher will accommodate an actual found server with the connection mode, which the client requested, by relaying data appropriately and in a way suitable for the server.

Note: FIREWALL indicates that the client chooses a firewall method of communication.

Note: Some server types can be ignored if not compatible with the current client mode |

Client-Mode: <client-mode> |

The <client-mode> can be one of the following:

STATELESS_ONLY - specifies that the client is not capable of doing full-duplex data exchange with the server in a session mode (e.g., in a dedicated connection). STATEFUL_CAPABLE - should be used by the clients, which are capable of holding an opened connection to a server. This keyword serves as a hint to the dispatcher to try to open a direct TCP channel between the client and the server, thus reducing the network usage overhead.

The default (when the tag is not present at all) is STATELESS_ONLY to support Web browsers. |

Dispatch-Mode: <dispatch-mode> |

The <dispatch-mode> can be one of the following:

INFORMATION_ONLY - specifies that the request is a dispatching request, and no data and/or connection establishment with the server is required at this stage, i.e., the DISPD dispatcher returns only a list of available server specifications (if any) corresponding to the requested service and in accordance with client mode and server acceptance. NO_INFORMATION - is used to disable sending the above-mentioned dispatching information back to the client. This keyword is reserved solely for internal use by the DISPD dispatcher and should not be used by applications. STATEFUL_INCLUSIVE - informs the DISPD dispatcher that the current request is a connection request, and because it is going over HTTP it is treated as stateless, thus dispatching would supply stateless servers only. This keyword modifies the default behavior, and dispatching information sent back along with the server reply (resulting from data exchange) should include stateful servers as well, allowing the client to go to a dedicated connection later. OK_DOWN or OK_SUPPRESSED or PROMISCUOUS - defines a dispatch only request without actual data transfer for the client to obtain a list of servers which otherwise are not included such as, currently down servers (OK_DOWN), currently suppressed by having 100% penalty servers (OK_SUPPRESSED) or both (PROMISCUOUS)

The default (in the absence of this tag) is a connection request, and because it is going over HTTP, it is automatically considered stateless. This is to support calls for NCBI services from Web browsers. |

Skip-Info-<n>: <server-info> |